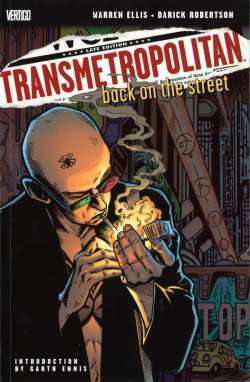

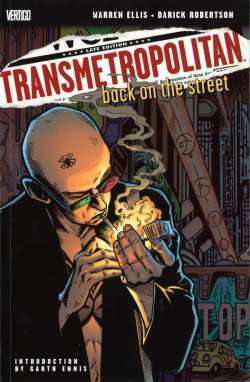

Transmetropolitan isn’t just an obscenity laced Sci-Fi depiction of Hunter S. Thompson designed to appeal to a ’90’s aesthetic.

It’s a Comic Book about Comic Books, too.

For some of us, we were younger men, once. Angry, frustrated, hormonal, embodying a high-octane version of a Rocket From The Tombs tune. We would read Bukowski and we drank whiskey in bars and we walked around aimlessly at night as if we could walk forever, in any direction, until life (capital L) hit us in the face. We would swap drug stories and leered at pretty girls and watched Bogart movies and read Fear & Loathing periodically to remind ourselves of the good times, as you often found yourself in meaningless intellectual pursuits to help pass the endless gulfs of time that besieged us each and every day.

We kept journals in those days. Drunken, sprawling, bawling journals. Don’t let anyone try and tell you otherwise.

As a younger man, you are capable of great cynicism, great misery, great exaggeration, great obscenity, and even great solipsism, with the practice 21 to 35 offers. You think in distracted, overstimulated fits & spurts. Every idea burns with the newness of unfiltered pornography. You imagine more and more horrible things as you test the limits of your own depravity, or at least what you think you can stomach. Younger men are pretty sure there is no god, the are pretty sure their family has abandoned them, and to prove all of this, they test the limits of those notions, of language, or fashion and sexuality, trying to figure out what you can get away with, and what you’ll let yourself get away with. In your wildest imagination, boundaries – all boundaries – seem arbitrary, and defined only by the slightest hint of recognition that you happened to cross it, intentionally or otherwise.

It is from this place that Warren Ellis & Darick Robertson have taken up residence, so they can stew in the juices of youthful anger and incensed outrage in only the way that a young person who has taken up pen and paper can. But, unlike a 20 something male with a xerox machine and a ‘zine they shove into the hands of his increasingly-annoyed-friends to read later, Ellis & Robertson focused that energy into the creation of Spider Jerusalem, a proxy for their unchallenged Id’s. To deliver a character like this with the kind of venom of a gonzo journalist was no small thing, and together they made a handful of overly ’90’s choices in assembling Spider’s universe. Sci-Fi alone could fly almost anywhere, and Hunter’s attitude toward politics was certainly becoming known to the general public more at that period. But to cram the two into a comic book world seemed insane, and could potentially muddy the message that either genre could convey in the medium. The only more iconic ’90’s choice they could have made would to be creating the book from the stage of Lollapalooza during a Porno For Pyro’s set.

For a smidgen of context: the ’90’s are the Gen-Xers ’60’s, and many of us want to claim that our drugs were better for you, and more powerful back then, and that our music was louder and more rebellious, and that, no matter how much you might disagree, our ideals were not temporary, but will stand the test of time, and we were not a… hey, why are you no longer listening to me and my tired, flaccid, invalid, 30-years-too-late rhetoric? As technology ramped up and politics entered our homes and lives through new media outlets, lefty ideals finally began to colonize popular culture through rock music, films and comic books, all wrapped up with a touring concert festival vibe that ran through our culture from 1986 until 1997. Our popular culture, so we thought, was so unique and generational that we failed to grasp the irony of how exactly the same-as-it-ever-was.

For businesses, generation trends like this always go over well, and as publishers realized that they could make a ton with a little branding, trade paperback collections of comics – “Graphic Novels” to the Barnes & Noble crowd – became the way many people were exposed to characters and stories. Books that didn’t have a chance to succeed in single issues suddenly had a life outside of direct market magazine sales on newsstands and in Comics Shops. Comics as a “hip” medium spread like wildfire to bookstores across the country in these new collections, and the same people that had reached for the Beats and Thompson twenty years earlier were now reaching for books by Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman & Grant Morrison, each of them depicting a sort of drug-fueled, rock star lifestyle that these UK Comics artists were bringing to the boring, super-hero dominated world that the last 20 years had delivered.

It was into this stew of cultural and social upheaval that Transmetropolitan hit the American consciousness, a book that really gained an audience only when it began to get collected into trades. As these were being viewed as “sophisticated reading” by those who were trying to make a buck off of youth culture, the upshot was that an experiment in comics narrative went on for nearly 70 issues, unprecedented for a story as weird & obscene, distributed by one of the big three publishers, no less (DC, natch).

Learning to Love The “F” Word (Comes with Accepting The “R” Word, Too).

Learning to Love The “F” Word (Comes with Accepting The “R” Word, Too).

There is an abrasiveness to the way Ellis & Robertson intentionally present Spider’s world, and it is not meant to win you over, if that’s what you’re hoping for. The last line to this first story arc in Transmetropolitan is, “I’m Spider Jerusalem, and Fuck all of you! Ha!” And as Spider looks at you, face bloody and beaten into a grotesquerie that is hard to stomach, he smiles, and it is easy to imagine that that he’s shouting this all directly at you, that you are specifically the person he is asking to “fuck off.”

And, in a way, he is.

Nothing is easy, sanitary, or in most cases, comfortable in this universe that we’re presented with, the least of which is the perspective of the main character. Together, Ellis & Robertson have envisioned much of what has actually happened to our world in the decade plus since Transmetropolitan stopped publishing, and if we keep moving at this clip, we’re on track for some of the grimmer parts of their projected future, too. Humanity, as these two see it, is still driven by the basest or impulses, barely able to look above the rim of their Ids at any given moment. The grimness is only overshadowed by the vulgar cleverness of this pair working together. They have found exactly the right balance of all ego/no filter, and have tailored the explicitness into 24 page “rage-poems” (the opposite of tone poems) about everything that is wrong, everywhere. This was the ’90’s zeitgeist – a generational criticism of the situation we found ourselves in – presented as a 4 Color Print comic.

Both Ellis & Robertson had careers before Transmetropolitan, but they met working for an indie company, and immediately gelled as creators. Ellis had this idea kicking around for a few years, and Darick seemed like he got it instantly. (A Sci-Fi Hunter Thompson who must keep the political goons in check.) Over the next couple of years they discussed and scripted Back On The Street, a three issue mini-series that introduced the character. When we meet Spider at the beginning, something feels fully formed about him, even from that primitive point in the early narrative. This might come from the years this character had been knocked about as the artists discussed him, but as I will get into later, I think it was Ellis & Robertson’s role as writers that may have more to do with it.

As a self-contained story, Back On The Street achieves a number of things. It sets up the potential series that Transmetropolitan could become: Spider returns to The City, get’s a job writing for a paper, and uses his column as a means to fight the wrongs of modern life. It also offers a B Plot: Spider is motivated to do this, largely because if he finishes his two contracted books, he can check out of modern life entirely and get back to his cabin, “up a goddamn mountain,” where he would prefer to be. All the while, there are layers upon layers of sci-fi gags and tropes in the background of every scene, which are usually themselves commentary on both everything and nothing.

And then, there’s Spider himself, the upraised middle finger of our story.

Spider barely qualifies as an anti-hero, in that there is no purer motivation for him except to get back to isolation and seclusion. His dedication to self-pleasure through drugs and alcohol, his preference for independence, his abusiveness to everyone around him at all times, and his over-use of rape imagery in his language (which, if I’m perfectly honest, makes me uncomfortable every time it’s used) makes Spider questionable as someone to identify with at best, and morally reprehensible at worst. He is an outsider in every sense, bound to no word or honor that the rest of the world accepts or acknowledges. Coming to The City seems like more of an attempt to give the system one good solid kick in the nuts before he can disappear completely than it is an attempt to resolve any kind of owed debt to his publisher. He is hardly a contestant for a 70 issue run of stories about his life, and is yet another barrier to entry that makes it hard to recommend the series who has anything close to a “delicate” sensibility.

So, if it is such an abomination to most pallets, why on earth write anything about it? Isn’t this a “you either like it or you don’t” kind of binary? Isn’t this Fight Club, or Lost all over again? What more could there possibly be to say about a series so foul and difficult to get into? To start with: the sense of humor. If you like your comedy like you enjoy your coffee, Transmetropolitan delivers in this category in spades. Granted, you have to be on-board with every permutation of filthy language, including the over use of words like Cunt and Rape and Fuck and every imaginable (and colorful) modifier. Ellis & Robertson take to profanity like Peter Capaldi in The Thick Of It, and not just in language, but in visual and narrative depiction, too. They love a good ribald joke, and to them, the funnier the filth, the better. So, a crude-oil-choking-animals-stuck-in-plastic-rings-black sense of humor is a huge part of the interest for most readers. But to me, even the jokes cover the more interesting bits.

Let’s Get This Out Of The Way (Here There Be Spoilers)

Let’s Get This Out Of The Way (Here There Be Spoilers)

To discuss Transmetropolitan with any more granularity requires spoilers, so I’ll just jump to the somewhat meaningless climax and get it over with: Spider types – in real time, mind you – a column so powerful that he stops an in-progress riot.

I shit you not; even in a Sci-Fi context, it is the primary definition of deus ex machina. (Let’s see me “write” my way out of this one!) But the plot in this particular story – like some of the best gonzo journalism – is more atmospheric than essential to what’s really going on. It’s the tone, the conviction, the character study, the word painting, of putting your faith in something that is A Good Cause in spite of your worst personality traits, the TRUTH (or whatever) at any cost… it’s putting on the page some flavor of honesty in whatever form you can, be it journalistic or comic-book-ic. Robertson & Ellis both loose the story in one hamfisted detail or another along the way. And with Back On The Street, they shoot the moon on the first try, which is admirable AND foolhardy.

And, to me, that is the point, too.

In the course of Back On The Street, we find out that Spider has sequestered himself “up a god damn mountain” in a rural part of the world, living with little communication for the last five years, lost in a drunken, drug-fueled solitude that he’s been quite enjoying, selfishly. He is coaxed out of this reverie because he still owes an ex-publisher two books. Spider returns to The City, where he obtains a columnist gig immediately based on his reputation, and his first story is following up on an old friend, Fred Christ, who leads the Transiet Movement. (These are people who are transitioning from human to alien.) Fred incites two of his people to start a riot to get some press about the way the transients are being oppressed. Spider covers the story live, forcing the cops (who are engaging in the riot) to stand down. During the riot, Fred is found to be a fraud, rapist and pedophile, and Spider is beaten by the cops outside his own home to teach him a lesson about getting in the way of real power. Spider joyously rises up from the ground in the last scene, laughing triumphantly, happy to be back on the job in The Glorious City.

Roll credits.

As a story, it’s not bad, and it was clearly enough for the publisher to get the ball rolling, and give Ellis & Robinson a series. (It was just as likely that the series would forever be remembered for the three-issue run, too.) But when you get to the next collected volume of comics in the series, you realize it it isn’t even the greatest Transmetropolitan story, let along a great beginning to a series that changes and evolved over time. More than anything, Back On The Street reads like a foul-mouthed, pro-drug diatribe, a manifesto with plot holes and idiosyncratic views on government and politics that is somewhere between a comic series and Police Evidence.

However, when the series began to get collected in trades, we know that Spider became a bit of a phenomena all over. Clearly, this book spoke to an audience that was being rewarded for looked for further meaning in the series, and it’s clear there is something else going on here than just a string of comic book profanity. Ellis & Robertson are pointing their sci-fi barbed ideas directly at the current American Dream, and their commentary has only become more relevant as time has gone on, but was on the minds of everyone in the ’90’s. The representation of journalism as a narcotic-inspired sprint from interview to interview, only so the publisher can participate in some devolved version of political discourse – in spite of what’s happening in a city overrun by vandalism, poverty and inequality – even at this far-future date of 2015 seems eerily on point for what is now almost a 30 year old series. Throw other hot topics that are not even the main subject of the story – issues of trans culture, cult leaders, police brutality, and invasive species – and you’ve only sort of scratched the surface of what Transmetropolitan is all about, on one level.

Nobody comes out of Back On The Street looking good. Spider stops the riot, but is beaten for the effort. The trans movement gets press, but their spokesperson is revealed to be a sex-crazed pedophile who joined the movement to get tail and make money. The police are clearly on the take, and easily manipulated, but this only makes them even more dangerous than originally intended. Even Royce (Spider’s editor) goes from ‘doing Spider a solid’ to milking his popularity and brand as a way to make a lot of money. As mentioned above, the book makes it hard to like the story through obscenity and other prickly presentations, and so if there is an appeal to the book, it must come from Spider’s personality. Or rather, his resemblance to Hunter Thompson in behavior. It is from this angle that the character – and the series – starts to come into intellectual focus.

Transmetropolitan is best summarized as a Sci-Fi depiction of a Hunter-like character in an undisclosed amount of time in the nearish future, and this has been the back-cover-blurb short-hand for what the series is about since its inception. It is a summary that Ellis & Robertson have tried to shake, doggedly. Still, it is a decent enough jumping on point if you are trying to find a way to pick up this series, and if you are not on board with that basic concept at first, it is likely nothing can attract someone who is wondering if they’ll like the book. Admittedly, people may like Spider for the ways that he is different than Hunter: Spider is much more jovial, and seems to be having fun as a journalist, and seems to enjoy the physical benefits of the surreal insanity of this future world, unlike Thompson, who seemed to despise modernity in all its forms. It seems that, rather than to use Hunter as a direct inspiration for our protagonist, they have inverted his archetype to distance Spider from this part of Hunter’s character.

Transmetropolitan is best summarized as a Sci-Fi depiction of a Hunter-like character in an undisclosed amount of time in the nearish future, and this has been the back-cover-blurb short-hand for what the series is about since its inception. It is a summary that Ellis & Robertson have tried to shake, doggedly. Still, it is a decent enough jumping on point if you are trying to find a way to pick up this series, and if you are not on board with that basic concept at first, it is likely nothing can attract someone who is wondering if they’ll like the book. Admittedly, people may like Spider for the ways that he is different than Hunter: Spider is much more jovial, and seems to be having fun as a journalist, and seems to enjoy the physical benefits of the surreal insanity of this future world, unlike Thompson, who seemed to despise modernity in all its forms. It seems that, rather than to use Hunter as a direct inspiration for our protagonist, they have inverted his archetype to distance Spider from this part of Hunter’s character.

This blurring of reality and fiction seems to be much closer to the goal Ellis and Robertson have with this book. Spider Jerusalem. Hunter Thompson. Their names are structurally similar, and even some of the physicality in Spider’s appearance is obviously meant to evoke the comparison between the two characters. But their personas are just different enough to create cognitive dissonance. Ellis & Robertson are giving us all the cues to expect a Hunter analogue, and deliver to us instead a much more exaggerated (and “comically” humorous) version of that expectation. As with all mysteries, Hunter is the McGuffin, but the the key to the mystery is still in the actual depiction of Spider. Just not in the way you think.

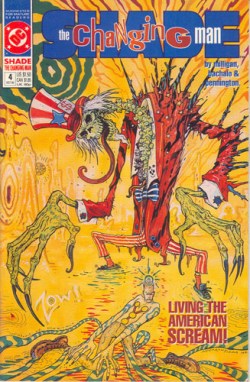

I Will Not Let This Devolve Into A Discussion Of Shade The Changing Man: Coming From Meta

The late ’90’s found a number of new styles, genres and authors rising to prominence as post-Grunge culture searched for their respective literary voices. The book that most resembles Transmetropolitan in form is The Invisibles by Grant Morsrison, which predates Transmetropolitan by a few years, yet they did run concurrently for a quite a while.  King Mob – the lead character of The Invisibles – is a dead ringer for not only Grant Morrison, but for Spider Jerusalem, coincidentally. (And, note the similarity in the form of their names, too.) This makes perfect sense in meta-narrative way. Spider’s look before moving to The City is a dead ringer for another, even older British author, Alan Moore. Through this meta-lens we can start to understand what Ellis & Robertson were driving at with this layered and obtuse story.

King Mob – the lead character of The Invisibles – is a dead ringer for not only Grant Morrison, but for Spider Jerusalem, coincidentally. (And, note the similarity in the form of their names, too.) This makes perfect sense in meta-narrative way. Spider’s look before moving to The City is a dead ringer for another, even older British author, Alan Moore. Through this meta-lens we can start to understand what Ellis & Robertson were driving at with this layered and obtuse story.

It goes without saying that Moore’s work on Swamp Thing & Watchmen (and, to an extent, his other DC work in the ’80’s) laid the groundwork for the ’90’s influx of UK talent. His reputation was equally legendary for his intelligent comics stories and his dedication to sex magic. His shamanistic appearance and tendency to incorporate poetry and blank verse as part of his narrative structure – and his larger use of literary collage as a well for inspiration – made him one of the first true auteurs of comics narrative writing. Many of his most well-known pieces of work were built upon his interest in borrowing characters, plot elements, genre conventions and song lyrics, all to assemble these parts into a dramatic story that was highly critical of power and government. The quality of the writing was of an intellectual caliber that exceeded what was prevalent in, say, the people who scripted, “Justice League,” to pick something at random. When you looked at the typical superhero fare of the era side-by-side with Moore’s work, it was hard to argue that he was anything less than inspired.

It goes without saying that Moore’s work on Swamp Thing & Watchmen (and, to an extent, his other DC work in the ’80’s) laid the groundwork for the ’90’s influx of UK talent. His reputation was equally legendary for his intelligent comics stories and his dedication to sex magic. His shamanistic appearance and tendency to incorporate poetry and blank verse as part of his narrative structure – and his larger use of literary collage as a well for inspiration – made him one of the first true auteurs of comics narrative writing. Many of his most well-known pieces of work were built upon his interest in borrowing characters, plot elements, genre conventions and song lyrics, all to assemble these parts into a dramatic story that was highly critical of power and government. The quality of the writing was of an intellectual caliber that exceeded what was prevalent in, say, the people who scripted, “Justice League,” to pick something at random. When you looked at the typical superhero fare of the era side-by-side with Moore’s work, it was hard to argue that he was anything less than inspired.

Morrison – a much more ’90’s figure in the world of comics – is not only a sort of namesake descendant of Moore (Moore-son), but to chart his own territory, took a different approach to the comics world through drugs and meta-text, placing his own overlay onto Moore’s framework for creating the perfect post-modern comics statement. Morrison’s stories also tended to have borrowed elements, but his characters were from comics own history, and are often aware of their own fictional qualities. Some of Morrison’s characters refer to themselves as “fiction suits” due to their physical similarity to Morrison himself, and these characters often make efforts to contact either the author or the reader directly, as the story demands. The Invisibles deconstructs spy narratives to the point of visual dissonance, and his runs on Doom Patrol and Animal Man defied both continuity and company policy in favor of post-modern jokes, and the search for the ‘creator / narrator.’ Morrison’s own theology seemed equally centered around hallucinogens in those days, but there is always an element of self-discovery and identity exploration at the core of his books. Trans lifestyles, government illogic, the inter-connectedness of all things all tend to work in concert with each other to create a non-linear, but impressive story.

Armed with this knowledge, the introduction of Spider’s character in Back On The Street suddenly carries with it a little more weight with it. As this bombastic and clearly educated character is up on the mountain, he leads a hermetic and drug-hazed lifestyle entirely focused on the self. Spider grows hair (that is usually eliminated by a normal shower in modern life). His attitude toward fans and the outside word is shoot-first, and his desire to have any public association with the work he’s done is nonexistent. However, his frustration with the world of publishing and modern life is not so strong that his book deal can’t draw him back to The City. The allure of writing a book on anything he chooses (once he writes the one about politics) awakens within him the need to pursue unfinished business. Each time Alan Moore agrees to work on a new book, it is not hard to imagine a similar phone call to the one Spider has at the beginning of Back On The Street.

Spider’s transformation into a Grant Morrison figure is made possible through the character of Royce, the managing editor of the paper. The role of editors in the world of comics plays a similar role to that of print journalism: take the writer’s material and massage it until it is ready for public consumption. Every book and major character at a comics publisher has an editor, and their role in making sure stories and titles get to the printer on time is not only necessary, but essential to coordinator with all the other writers and editors at a publisher. The shape of the final product, and the way we see the author that we read, is often the work of an editor.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but it might be worth it to include photos of Darrick & Warren to the images of Royce as depicted in Transmetropolitan. It is truly uncanny, and absolutely an intentional move. More directly a dead writer for Darrick (but also sharing a few of Ellis’ own visual cues), Royce is the filter through which the public is exposed to Spider Jerusalem. Royce keeps Spider’s ego – in its purest form – from reaching the audience, just like Stuart Moore at Helix Comics is the filter between the public and Warren & Darick’s raw vision for who Spider could truly be. (Stuart is referred to in the credits as “whorehopper,” a reference to the editor that holds Spider’s two-book contract, further blurring the fiction / reality border.) In just the drawings used to represent the main characters in the story, Transmetropolitan presents itself as pure metatext through using well-known comics writers to play out the drama. Once Transmetropolitan is read with a meta-text slant, the series really begins to reveal itself as something very masterful.

5: transitions.

Spider’s transition from an Alan Moore analog to a Grant Morrison analog is clearly meant to be seen as a cultural shift from one “older” paradigm to a younger, fresher one. Spider is moving from a purely creative position of integrity-in-art (Moore) to a position that must play the game, and learn to enjoy doing it (Morrision). On the mountain, Spider is merely a man, living alone, immersed in chemical abuse and the slow and steady detachment from the world around him in an almost spiritual pursuit of oblivion. Spider then traverses from the mountain to The City, where he is not only “plugged into” The City (as his devices come to life in the car as he gets closer, and can finally get a “signal”), but does so out of an obligation on the part of the writer to live near to where the publisher operates (a common practice in the old days of comics). But rather than work directly on his two-book contract, he instead starts an entirely new project with Royce, using the logic that he income from this new gig could help finance his work on the other contract that is due. (This is like the logic of using methadone to kick heroin.)

While we never see what Spider does on the mountain, its sounds as if he spent a lot of time in an altered state of mind, detached from the world. But when he comes to The City, he wants intelligence drugs, and the benefits of modern technology, to keep him focused on on point. His chemical intake shifts from oblivion to participation. Where Moore had become difficult to deal with, Morrison has become more and more dedicated to playing the game, a move that paid off in the long run. The style of dress is dramatically different, too. Spider wears old, worn and heavy clothes on the mountain, covering every inch of his body. It is somewhat funny, then, when Spider goes to his shitty apartment in The City, takes a “shower,” and it thus, baptized in light! He is reborn, now looking like Grant Morrison where he wears sleek, all-black “minimalist” clothes, where his form is easily revealed. Even his transition from the Mountain to The City is preceded by him blowing up the last remaining point of human contact he had before, and driving drunk into The City in a shitty car, barely acknowledging that he should be concerned about his behavior because he is ready to play the game.

The “two books” detail is interesting. Spider owes The Whorehopper a book about politics, and another of Spider’s choosing. This should be easy to Spider, who is not only a political journalist, but a prolific (and very famous) writer. But clearly this was difficult, so much so that he took the advance on this contract and retreated from society for five years to avoid writing either of these books, instead reading “Confederacy of Dunces” and “Fear And Loathing” over and over again. Spider has some sort of writer’s block, to a degree that is more severe than most. He not only can’t write, he is disillusioned with writing as a form of communication that can successfully change the world in a positive way. This problem is so pervasive that Spider can’t even muscle his way through a book on politics to get to the real gem, a book on any subject of his choosing. This can be seen as a metaphor for the book you have to do in comics to get a creator-owned deal, a common path for young writers, but also how things had worked out for both Ellis & Robertson, where Transmetropolitan was their “second” book.

6: Confusion between Referrer and Referent

The add to the ambiance of the world of Transmetropolitan, there is more than a bit of interplay between written bits that inhabit the world of Spider Jerusalem, and provide an additional level of commentary and meta-text to the book. The bar that Spider hangs out at is called “Bastard’s” (where they serve “Moore” beer). The rocket is branded “Eat Me,” and Spider’s license plate is alternately seen reading “Spider” and “Spyder.” The City is called City, and you can buy Exclaim Magazine! everywhere. Cop cars and taxi’s are easily identifiable, as their license plates read “Police” or “Taxi,” and the local paper is called “The Word,” and books are titled “Blah.” Signco produces all the signs in The City. The most popular brand of cigarettes are called “Stress Managers,” and all buildings are outfitted with AirCo brand air conditioners. Spider wears boots branded “Stomp,” and one man drinks a “Fuck You” brand liquor, straight from a bottle. The local strip club is called “Bazooms,” and you can get money from their “Cash” brand ATM. In a nod to Repo Man, beer is “A Can of Swill.” Computers tell you what they’re doing by printing “On” or “Recording” on their screens, and stairs are labeled with the place they lead to on their signs.

This language is difficult to classify in Transmet. They are not graffiti, not sounds effects, not dialog, and most likely, not meant to be “real.” Rather, these are all tiny jabs and barbs, little commentaries on how linguistic or world has become, but also to emphasize the symbolic nature of the item itself, in a medium already prone to meta-text. A police car with the license plate “Police” is too exaggerated and on the nose for most comics. But this book is trying to blur the line between reality and fiction anyway, and it makes sense that the world would just use these kinds of shorthands to continue that slide. Spider’s own view of the universe seems to be permeating the images we see, so much so that his reductionist perspective, he’s fleeting commentary, and his disdain are all captured in these kinds of uses of text.

7: The Message Behind The Meaning

Ellis & Robinson are fairly casual when it comes to referring to the social, political and ecological problems that plague Spider’s universe. In many ways, the problems are largely irrelevant, and only occasionally push their way into the narrative forefront. However, what is unique about these references is that, in the hands of most other Sci-Fi authors, the entire story would be subsumed in these secondary (and tertiary) references that liter the story in Transmetropolitan. There seems to be little to no control over guns, as they are everywhere, used liberally, and with seemingly no consequences. (Spider has a rocket launcher and grenades that are used often.) Traffic is not only a continuing problem in the future, but there are actual standstill days where people like Spider just get up, abandon their cars, and walk. Advertising is ubiquitous and on every surface imaginable, in every size, blocking any and all skylines The City every used to have. Geckos are an invasive species that has become an incredible problem in The City, so much so that mutant feral cats have been genetically altered to hunt and eat only Geckos. Every home is equipped with a “Godti” maker, that can materialize our every need. The only problem is the machines often get hooked on drugs.

Glossed over quickly in the first three issues: Trans Culture, Drug Abuse, Ghettos of the Future, Cult Leaders, Rape, Child Abuse, Cameras Invading Every Last Privacy, Age Restrictions In Bars Lowered to 17, Ridiculous Future Fashion, Police Brutality, Bar Codes Replacing a Stripper’s Nipples, Journalistic Integrity vs. Journalistic Terrorism, and the continuing slide of human apathy. And all of this – and more that I missed, I’m sure – are crammed into three issues. The denseness of what is happening in every panel of Spider’s world is directly connected to his hatred of life in The City. He curses the moment all of his “devices” activate as he gets closer to The City, and he becomes a distracted and ferocious driver. The sound of The City makes him question his return, and speaks to the tangle of issues that Spider can’t completely engage when he is forced to face them head-on.

These is clearest when Spider meets up with his soon-to-be editor, Royce. When they are together, they yell and scream and smoke and swear for most of the interaction, but when Royce corners Spider – Editor to Writer – and asks why Spider left, and while he points a gun at Royce’s forehead, says, “The fans, Royce. The fans and the noise and the bullshit and… I couldn’t get at the truth anymore,” to which Spider puts down the gun, for one brief second, absolutely vulnerable.

This is the most precise interpretation of the creative process I’ve ever seen portrayed in comics: you’re manic creative side violently rebelling against the organized editor only because you’re insecure about how honest your work actually is. It is really the only time you see Spider emote earnestly, and only when he’s concerned about being a fraud. It not only offers another dimension to his character, but also seems to be a bit of a plea on the part of the authors: we’re going to strip things down, bare, in an effort to be as honest as possible. But to do so, we’re going to have to make light of some social issues. We’re gonna use course language. But this is all metaphor, a way to analyze the creative process, creatively. Let me take my guard down for a moment, and maybe we can go on a journey together?

Spider and Royce and a fascinating relationship. Royce begins every conversation with, “Where’s my fucking column?” in spite of the fact that it is only two hours after he hired Spider to write for him. Of course, Ellis & Robinson can’t resist a bathroom joke if they can help it, so at this point in the story, Spider is on Jumpstart, and has taken to keeping the phone in the toilet bowl (since he doesn’t use the bowl anyway, and since this location reflects how he feels about the phone, since only Royce can call him anyway). Spider furthers by asking his adopted gecko-eating cat to piss on the receiver in lieu (hold for laugh) of a proper hang up. The scene is played for laughs, but this is just after Spider has cleaned himself up, and is looking for a story to write. Spider is constipated in more ways than one, and in spite of trying, he has yet to write a single word.

8:

In yet another turn of inappropriate humor, Ellis and Robinson decided that the climax of Back On The Street happens on the roof of a strip club, while strippers watch Spider – ahem – pull off a live story while he watches a riot. It makes sense that Spider feels at home at a strip club, as he sees his own work as prostitituion, and finds no problem with that lifestyle for anyone. The metaphor continues as Royce watches Spider’s live-feed coverage of the riot, and Royce’s eyes glaze over, as if he’s watching porn. Royce immediately monetizes what Spider is doing on the live-feed, pimping out Spider’s words like anyone else does.

But what makes this scene incredible – and appropriate to our discussion at hand – is the way in which Spider is depicted in the panels where he is “live blogging.” Spider’s face contorts into every possible facial expression: joy, anger, bemusement, epiphany, sweaty-clenched teeth, half-closed eyes as smoke snorts out his nose, so into the moment that he is barely aware that the riot has “climaxed,” and shut itself down, while he is still pounding away on the keyboard, lost in the moment of textual release. Afterward, exhausted and with a sad-but-spent expression, he passes out in the open hand of a hooker. Or, at least, the sign outside the strip-club designed to look like one. As the police leave the scene of the riot, Spider remarks that, “they’re pulling right out.” More telling, the stripper refers to Spider as “fuckhead.” He’s not having actual sex. He’s fucking “in the head.”

Bedroom humor aside, the point is made that Spider walks past all four strippers (who don’t seem to do much for him), and is much more turned on by his relationship to the written word. To him, it is the drug, the thing that gives him a mainline jolt, and fills him with horror and humor and joy and desire. In this section, we are given the whole of Spider’s Id in all of its playful, graphic, privileged wonder. In a lot of ways, what is printed here is irrelevant, and I went through it a few times for pull-outs or lines I could use to sway my position. But, ironically, they only paint a picture of Spider, not the event at hand. The “live blogging” plays a role in the plot, to be sure. (The police leave because of it.) But what is blogged is lost, and instead what is revealed is that Spider’s only joy, his only release in this world is writing what he sees around him, as honestly and as directly as possible, and only then will he feel any respite from the nagging problems of everyday life.

This, of course, is at the center of the Ellis – Robinson thrust of Transmetropolitan. The meta-text and inside-comics-baseball structure of the story – and the way in which every moment can be pulled apart for a layered commentary on writing, and specifically Sci-Fi-gonzo journalism – is a mission statement from the creators to offer up a perfect cross-section of what the book will be about for the next 67 issues. Ellis and Robinson are interested in the struggles of The Writer. The work they produce. The relevance they serve. And what about Comics? Can it get political? Can it be “gonzo”? Ellis and Robinson want to get as close to the metal as possible, and this means taking their stories through multi-layered bathroom and masturbation jokes, by turning environmental shortcomings into one-off jokes. They want the writer to be the main character, to focus on his problems and difficulties. Who hasn’t felt, at that moment of creation, like the smoking and snorting Spider from the climax of Back On The Street? Only, later, to realize you’re just a guy, drunk and watching the world, and trying hard to reflect into text how you feel about it.

9:

It is easy to sell short Transmetropolitan for the shortcomings. It is very ’90’s, in style and presentation, and while Spider seems righteous, he can wear on your nerves, absolutely. But to dwell on Spider as a character sort of misses the point. This is a study in writing – about what writing can do, where it can go, and what it can tell us. This is a study in form, both comics and journalism, contextualized through the tropes and ideas of Sci-Fi. This is an attempt to see if this kind of writing can be done, and to break it down as the series progresses. Spider is, in many ways, secondary, because at the center of Transmetropolitan is a love-letter to pitfalls of the creative process, and that is the greatest strength of this book.

The humor, the art, and the large upraised middle finger to all expectations and conventions are merely icing on the cake.

Spider lives on the 1600 block,

King Mob – the lead character of The Invisibles – is a dead ringer for not only Grant Morrison, but for Spider Jerusalem, coincidentally. (And, note the similarity in the form of their names, too.) This makes perfect sense in meta-narrative way. Spider’s look before moving to The City is a dead ringer for another, even older British author, Alan Moore. Through this meta-lens we can start to understand what Ellis & Robertson were driving at with this layered and obtuse story.

King Mob – the lead character of The Invisibles – is a dead ringer for not only Grant Morrison, but for Spider Jerusalem, coincidentally. (And, note the similarity in the form of their names, too.) This makes perfect sense in meta-narrative way. Spider’s look before moving to The City is a dead ringer for another, even older British author, Alan Moore. Through this meta-lens we can start to understand what Ellis & Robertson were driving at with this layered and obtuse story.